Diamond Peak: A Hidden Gem with a Rich History

By Mark McLaughlin

Diamond Peak, which is celebrating its 60th anniversary this winter, is probably the most overlooked and underrated ski resort in the Tahoe Basin. With an impressive 1,840 feet of vertical, a variety of easy or challenging trails and breathtaking views of Big Blue, Diamond Peak is without a doubt a premier Tahoe ski destination. This hidden jewel boasts miles of uncrowded runs, open tree skiing, and an intermediate cruiser called Crystal Ridge that is rated among the “World’s 100 Best Ski Runs” by CNN Travel.

Diamond Peak is geared towards an exciting family experience, but diehard skiers can challenge themselves in Solitude Canyon and the Glade Zones, a series of expert tree-skiing areas that are killer after a powder storm. Located east of the Sierra Crest, Diamond Peak gets plenty of snow with more than its share of sunshine too. The resort has something for everyone with 18% beginner, 46% intermediate and 36% advanced runs.

Diamond Peak is owned and managed by the Incline Village General Improvement District, the local governmental agency tasked with providing water, sewer, trash and community recreation for the communities of Incline Village and Crystal Bay.

Diamond Peak is owned and managed by the Incline Village General Improvement District, the local governmental agency tasked with providing water, sewer, trash and community recreation for the communities of Incline Village and Crystal Bay.

Because of this community ownership model, the resort boasts a modern top-to-bottom snowmaking system that covers 75% of the resort’s developed terrain. A fleet of state-of-the-art PistenBully grooming machines sculpts the runs each night, equipped with SNOWsat, a professional fleet and grooming management system with snow depth measurements based on satellite guided positioning which facilitates more effective grooming.

From timber production to alpine skiing

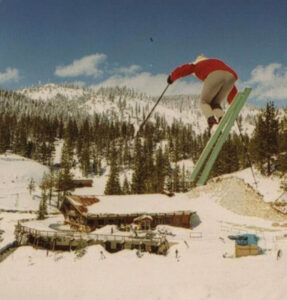

An early ski patroller on a powder day at Ski Incline

Like many Tahoe ski resorts, Diamond Peak has an interesting history. During the late 1800s, the region was logged of its timber to support the Comstock mining boom near Virginia City, Nevada. The first major timber mill at Lake Tahoe was located near South Lake Tahoe at Glenbrook, Nevada, but in the far northeastern portion of the Tahoe Basin another sawmill was built at Mill Creek by the Sierra Nevada Wood & Lumber Company. Following construction of the mill, the company’s general manager, Captain Overton ordered his crews to build what he called the “Great Incline of the Sierra Nevada.”

Overton engineered an 18-foot-wide narrow-gauge tram to run cut wood straight up the side of the mountain just east of Mill Creek, similar to alpine funiculars and cable car railways of the time. Cord wood and cut lumber harvested from forestland along the North Shore were loaded into tram cars and hauled 1,400 feet up to Incline Summit by the double-track tramline.

The slope was so steep near the top that the maximum track gradient reached an amazing 67%. Built in 1880, this steam powered cable railway was 4,000 feet long and became known as “The Great Tramline of Tahoe.” The Incline tram was so spectacular that steamer captains ran special excursions past the area because their passengers wanted to see it in operation.

Powered by two massive 12-foot diameter iron bull wheels, the innovative logging operation inspired the moniker “Incline.” Just below the ridgeline of Incline Summit, the lumber and cord wood were unloaded from the trams and tossed into a water flume that carried the wood products to a lumber yard near Washoe Valley for pick-up and delivery by the Virginia & Truckee Railroad.

The short-lived settlement of Incline Village formed on Incline Creek in 1882, but by 1897 nothing remained there except for stripped forest land, logging roads and crumbling flumes.

A skier catches air on Show Off run with the Base Lodge in the background.

For the next several decades the area took a back seat to flourishing summer home developments at Glenbrook, Tahoe City and near Tallac south of Emerald Bay. Despite fits and starts, alpine skiing at Incline was still nearly 70 years in the future.

There was a flurry of activity in the late 1930s when it seemed that lift-served, downhill skiing was about to become a reality near Incline. Norman Biltz, owner of the Cal Neva Lodge in Crystal Bay, had returned from Europe where he was inspired by the possibility of building an Austrian-style resort at Lake Tahoe.

In early August 1937, Biltz organized a team to produce a feasibility study for developing nearby Rifle Peak (elevation 9,488 feet) into a ski resort. The recently opened, celebrity-studded Sun Valley ski area in Idaho showed Tahoe’s potential.

Joining Biltz for the exploration of Rifle Peak was noted Reno architect Frederick De Longchamps, freelance Reno ski journalist William B. Berry, a bevy of engineers, and local skiers Halvor Michelson and Wayne Poulsen.

A preliminary report on the proposed ski site was released a few weeks later, but more detailed information regarding the mountain snowpack was needed.

Wayne Poulsen, future founder of Squaw Valley, was a seasoned snow surveyor under the tutelage of Dr. James Church, developer of the Mt. Rose Snow Sampler. To study the site in winter conditions, Poulsen spent much of the 1937-38 season on top of Rifle Peak where he scouted skiing terrain and snow deposition. He was working with Biltz in this effort to develop an alpine ski area accessed by cable car from near the lake.

Poulsen and his buddies from the University of Nevada-Reno ski team had built crude cabins at the summit out of old flume wood for winter shelter. That winter, the snowiest on record in the Tahoe Sierra, Wayne lived off canned stew that his skiing friends would bring him periodically. Poulsen had long been familiar with the area because when he was in the Boy Scouts, every winter his Reno troop hiked on skis from Galena Meadows, over Mt. Rose and then down into present day Incline Village.

Skiers admiring the views from the slopes of Ski Incline

The Rifle Peak project caught the attention of Captain George Whittell, an enigmatic San Francisco real estate tycoon who owned most of the Nevada side of Lake Tahoe. In the summer of 1938, Whittell proposed building a $1 million casino and hotel resort at Sand Harbor in hopes of cashing in on the much-anticipated Rifle Peak ski development, but the savvy investor was waiting to see how successful Norman Biltz’s winter sports program would be. Although Biltz and his partners envisioned ski runs, jumps, tramways and tows, lodges, bobsledding, ice skating and other related winter activities in their “Tahoe Alps” project, Rifle Peak was the key cog in the whole plan.

Unfortunately, Wayne Poulsen came down from the mountain reporting that Rifle Peak was poorly suited for a ski resort. The southern exposure and proximity to Lake Tahoe resulted in a wet, unstable snowpack; and that in many years the snow on the lower elevations would melt too quickly in the spring.

The United States’ entry into World War II would be the final nail in the coffin for the dream of a networked “Lake Tahoe Ski-Way.”

In 1960 George Whittell sold 9,000 acres of his land to Art Wood, an Oklahoma-based developer. Wood and his associate Harold B. Tiller envisioned the creation of Incline Village – a master planned vacation resort community. A cornerstone amenity for this concept was a new ski area called Ski Incline.

It was a stroke of genius that Art Wood hired legendary Austrian ski pioneer Luggi Foeger to design and build the $2 million ski area. When Foeger looked over the initial layout of the project, he told Wood that the location was all wrong from a skier’s perspective.

The original proposal situated the resort on the slopes of Rose Knob Peak, a high-elevation flat-topped ridge not far from Rifle Peak. Foeger argued that the proposed runs were too steep for beginner and intermediate level skiers and the slopes faced south instead of north, which better protected the snow. And in Foeger’s mind, the proposed runs were poorly cut.

Foeger successfully re-designed Ski Incline “to provide a pleasurable experience for the whole family.”

Over his career he had headed ski schools at Badger Pass in Yosemite National Park, Sugar Bowl and Alpine Meadows at Lake Tahoe. He also helped design Northstar California, now owned by Vail Resorts.

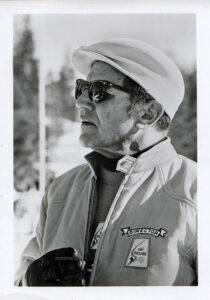

Luggi Foeger – Mastermind behind Ski Incline

Ski Incline founder Luggi Foeger

In 1940, Minot “Minnie” Dole, a Connecticut insurance broker and ski enthusiast who had previously organized the National Ski Patrol System to help injured skiers, convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the U.S. War Department that the Army desperately needed a unit of mountain soldiers to fight in the high mountain country of Europe during World War II. The War Department asked Dole to utilize the Ski Patrol System to recruit skiers and mountain climbers from all over the country.

Any man who wanted to enlist as a ski trooper needed three written letters of endorsement testifying to his skiing ability and wilderness experience and skills. Recruiters encouraged all outdoor-oriented men to volunteer for mountain soldier training at Camp Hale, Colorado.

Park rangers, trappers, hunting guides, and ranchers signed up. Among the brave volunteers who joined were two former Truckee, California residents, the late Karl Kielhofer and Pete Vanni. Roy Mikkelsen, a national ski jumping champion with the Auburn Ski Club, was a second lieutenant at Camp Hale in 1943. Bill Klein (a longtime director of skiing at Sugar Bowl Ski Resort) also joined the mountain unit.

After the war, veterans from the 10th Mountain Division fired-up America’s modern ski industry. They published ski magazines, managed ski shops, opened ski schools, designed and marketed ski equipment, and established ski areas, including Vail, Aspen, Sugarbush, Whiteface Mountain and others. At least 62 ski resorts have been founded by, managed by, or employed Head Ski Instructors that were veterans of the 10th Mountain Division.

As a young man growing up in Austria, Luggi Foeger had flourished as a prodigal skier and mountaineer in that country’s rugged Tyrol region. For 10 years, he was also a top instructor for Hannes Schneider in St. Anton, Austria.

Schneider is known as the “father of modern ski teaching” for his development of the Arlberg Technique where alpine skiers crouch and bend their legs with weight forward to initiate smooth turns.

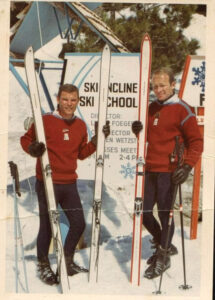

Ski Incline’s second GM was Jurgen Wetzstein (pictured left)

During World War II, when he was in his early 40s, Foeger fled to the United States to escape the Nazis. After the war, he joined a select group of experts teaching skiing and winter survival skills for the ongoing 10th Mountain Division. Foeger later moved to California to run ski programs in the Sierra, starting out as the Director of the Ski School at Yosemite’s Badger Pass.

The affable instructor was known as much for his sense of humor as for his care in resort design to preserve and protect the environment, while at the same time cultivating thoroughly manicured slopes for good skiing. Skiers who knew Luggi Foeger rated him as “one of the true complete mountain men” of the world.

Foeger, who died in 1992, was inducted into the prestigious National Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame, an honor that represents the highest level of national achievement in ski sport. Indicative of their influence on the United States ski industry, there are a total of 34 10th Mountain Division veterans whose names now appear in the Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame.

Foeger’s award-winning layout of Ski Incline was called a model for modern ski slope development. Foeger’s wife Helen said, “Luggi wasn’t as interested in advanced skiers wanting to find new challenges. He worked more to develop skiers, and design runs that everybody could enjoy. He did a wonderful job.”

Snowmaking and upward expansion

Old Ski Incline snow gun and snowmobiles

Ski Incline was the first resort in the West to utilize a snowmaking system, and when it opened on November 19, 1966, it featured three chair lifts, a T-bar surface lift and nicely groomed terrain.

Among the many skiers who visited that first winter was the popular American television entertainer Art Linkletter. Linkletter skied all over the world, but he loved the resorts at Lake Tahoe best.

Known for his humorous TV interviews with children in the 1950s, and writing the bestselling book, “Kids Say the Darndest Things,” Linkletter was also a remarkable athlete who first began skiing at age 50. He loved it so much he skied competitively in senior races until he was 93 years old.

Art was finally forced to give up the sport when he returned from a speaking tour to discover that his wife had given away all his equipment, saying she “wanted to be a wife, not a nurse.” Art always said, “Skiing is the closest thing to flying and dancing.” He got that right.

Ski Incline was known as a great place to hold ski races throughout the past 60 years.

In the 1980s, improvements at Ski Incline added more chairlifts and expanded snowmaking capability. Then in 1987, under the direction of Ski Resort Manager Jurgen Wetzstein, the area doubled in size and was renamed Diamond Peak, to highlight the addition of longer, more advanced runs on the new upper mountain. The addition of the mile-long Crystal Quad chairlift to the summit was icing on the cake. (See the accompanying story “Diamond Peak: Built By Hand” in this edition for more details on this expansion project.)

Since then, over $30 million has been invested in capital improvements that produced a new high-speed detachable Crystal Express chairlift that cut the ride time to the summit in half, beautifully renovated lodges in the base area, a state-of-the-art grooming fleet and a more efficient snow making system.

From a skier’s or snowboarder’s perspective, the resort was laid out with an experienced eye. While ski areas generally pitch their vertical statistics from a topographical viewpoint of maximum elevation change from top to bottom, there are many mountains at which it is impossible to actually ski from the highest point to the lowest point, so the measurement has limited practical value. Based on real skiable vertical, Diamond Peak ranks fourth among Tahoe resorts for the continuity and skiability of terrain between those high and low points — ahead of such notable resorts as Mt. Rose, Homewood, Alpine Meadows and even Kirkwood.

Diamond Peak is celebrating a big “Diamond” anniversary season this year. Make sure you join the party!

[Note: This story first appeared in the IVGID Quarterly 10 years ago when Diamond Peak was celebrating its 50th anniversary.]

About the author

Tahoe historian Mark McLaughlin is a nationally published author and professional speaker. His newest title, “SNOWBOUND! Legendary Winters of the Tahoe Sierra” and other award-winning books are available at stores in the Basin or at TheStormKing.com. Mark can be reached at mark@thestormking.com and you can check out Mark’s blog at TahoeNuggets.com.